Here’s a question that actually makes you wonder: are you who you are bound up in your memories? To ask seems to be at the very root of what it means to be human. I mean, memories aren’t really histories of what occurred, are they? They’re the bricks of everything, our continuity, our relationships, our moralities, even who we think we are. So if we did lose everything, would we even be us anymore? Or is something more at work that we just can’t get our heads around?

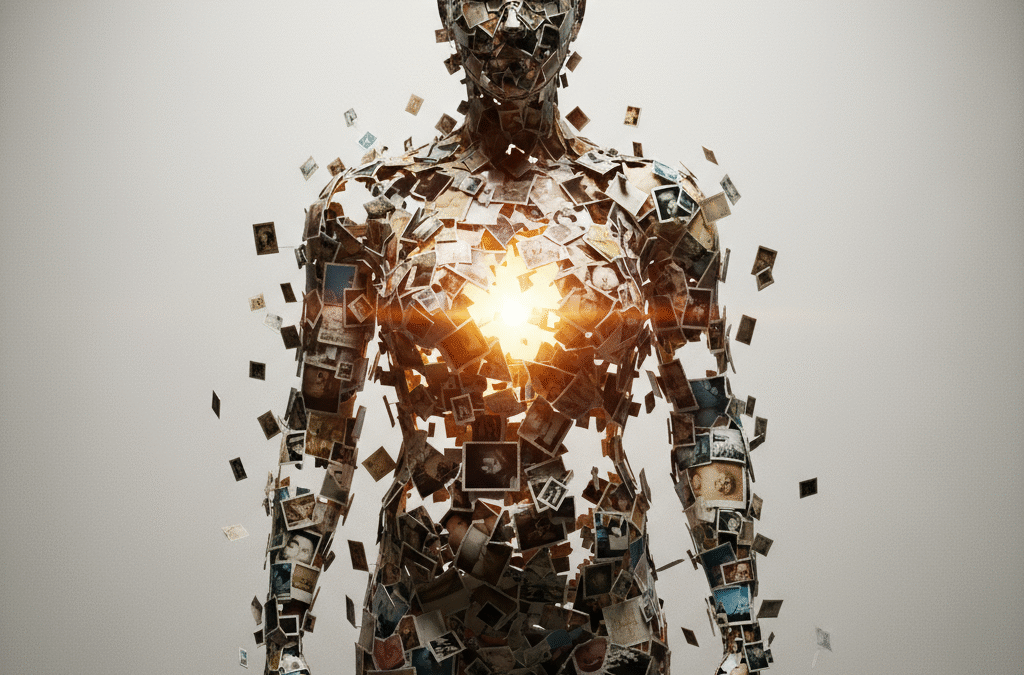

On the surface of it, actually, it really does seem like memory is the whole shebang. Think about it: when you introduce yourself, you’re basically telling a story made up of memory, your childhood, your victories and failures, all the blisses and hurts that made you who you are. These are the times that give you a narrative that makes your life come together, enabling you to connect the past you and the present you. In one sense, memory does not simply retain the past; it stitches all of those fragments of existence into a whole. Without memory, our life history would literally fall apart into an enormous quantity of unrelated moments, with no meaning at all.

It’s especially tragic when you think about diseases such as Alzheimer’s or amnesia. When the memory starts to fade away from a person, their loved ones will say to you, “they’re just not the same person anymore.” It’s like the self just vanishes along with the memories, leaving behind a body and the shadow of a person who was. When it happens that way, the sense is collective: without that strand of self, we’re adrift.

But hold on a minute, maybe we’re rushing it. Identity isn’t about memory. Suppose that there’s a “core self,” that inward self that’s all hidden behind the remembering. Even if an individual does forget their conscious memories, they still have their own way of being, their habits, their instincts, their tiny mannerisms. The amnesiac subject might laugh just the way he once was, be just as sympathetic, or just as strange as he was before. And when the memory is gone, there is something left behind, a kind of personal facet of who they are that could not be boiled down to memory.

This presents a philosophically challenging issue: what’s the real basis of identity? Is it psychological continuity, or something more basic, even consciousness itself? John Locke famously thought that personal identity was just a function of memory. In order to be the same person, you have to remember what you used to be. But that gets us into trouble. If I forget some childhood memory, am I no longer the same person I was as a child? No one would accept that. It only illustrates how important memory is, but it’s not everything.

Maybe identity is not such a simple thing either. Memory is the string weaving in and out of our tale over the centuries, but underneath there’s a more primitive feeling of just being there, the plain fact of existing. So even without memory, we’re still here beings, still in the here and now. And in that sense, identity perhaps never is lost with memory; perhaps it merely transforms into some new form, less a narrative about who we’ve become, and more of a defiant engagement with life itself.

Finally, whether or not we are “ourselves” without memory is a question of what we mean by the term “self.” If the self is only a narrative, then certainly memory is everything. But if self is the persona of a mind, then memory is part but not the persona. I think what the real answer probably is, though, is that it’s sort of both. Memory clearly does come into effect with how we see ourselves, but identity is so much more than what we can recall. Its presence, existence, and the constant flux of life, even when completely divorced from the stories we tell of ourselves.