The “grandfather paradox” of time travel is reassuring in its simplicity: go back through time and ensure that your grandfather never met your grandmother, and you would never have been born. But if you were not born, who is going to go back in time and ensure that they did not meet? A cycle of paradoxes has been created, and now the entire web of causality begins to fall apart.

At one level, the paradox is a puzzle for scientists or science fiction writers. At a basic level, however, it’s incredibly philosophical. It leads us to question what it means for one event to “cause” another, and whether our own lives are a linear narrative or a twisted string that cannot be untangled.

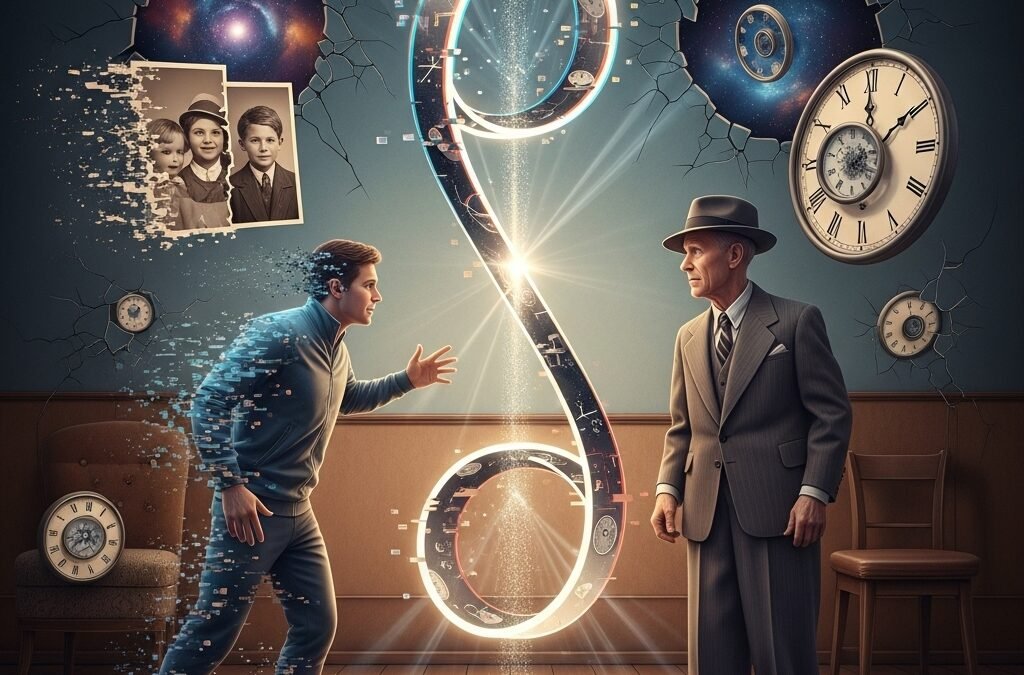

Time is something that occurs naturally to us, it runs on, moment to moment, like a river. The grandfather paradox, though, is an invitation we can’t help but accept to believe the danger that time is not a straight line at all but a fragile network of man. If causality can circle back upon itself and suffocate, then our own experience of sequence is nothing but a fiction that we construct to make existence make sense.

On a deeper level, the paradox questions whether we ever do manage to control the past. The fantasy of time travel is just the fantasy of redoing mistakes, reversing pain, restoring lost potential. But the paradox suggests that messing with the past is devastating to meaning itself. If anything can be withdrawn, then nothing can be established. If nothing can be established, can anything mean anything?

Philosophically, it boils down to fate and liberty. If time is predetermined, one massive tapestry long ago stitched, then we are less free than we think. Every event, every choice, every coincidence is already stitched into place. The grandfather paradox shows the cost of trying to pull out a single thread: the entire fabric unravels. But if time is not established, if time is something to be toyed with, then who are we but phantasms chasing bottomless pints of an infinite tale bereft of a beginning.

More sinister is the suggestion that the paradox is our own secret internal struggle against memory. How many times do we travel back into the past in our minds, living through moments, wishing for different words, different actions? On some level, we attempt “time travel” whenever we find ourselves mired in the contemplation of regret. But as with the paradox, the loop has us in its grasp: we can’t reverse what’s been done, but we can’t help but think that we can. The grandfather paradox isn’t really physics, it’s a metaphor for how stuck on the past we are.

There is no denying a certain beauty to the paradox itself. It teaches us that time, as we know it, is not so much a one-way street, if anything, but a labyrinth. Perhaps any attempt to alter it only leads us further into its intestines, and not out into farther. Perhaps meaning does not come from rewriting the past, but in embracing its absoluteness.

Finally, the grandfather paradox leaves us no neat resolution, only a mirror. It presents us with a mirror of our need to manage the unmanageable, to be uneasy with the one-way thrust of existence. Regardless of whether time is an arrow traveling in one direction, a circle, or an inconceivable mess, the paradox says the same thing: the past is lost and forever part of what we are. To be, then, not perhaps to conquer time, but to let it go.