Dreams have always vexed man because they remove the line between reality and fantasy, between will and necessity. In life, morality is entwined with responsibility: we are held responsible on the basis of decisions that we knowingly take, of intentions before our actions, and of harm or good which follows. But suppose we stumble into the land of dreams, where reason breaks, intentions distort, and actions unfold outside our control, do dream actions depict morally neutral fantasies, or do they reflect something real about who we are?

On the surface, it is absurd to hold individuals responsible for dream actions. After all, we do not dream at will, nor do we ask for the situations our minds generate. To condemn a man for theft, dishonesty, or even murder within a dream would be to condemn a storm for raining lightning. The dreamer is no more a legislator within the dream stream than a bystander, trapped within the current of fantasy. On this basis, dreams have to be above morality, products of fantasy mental theatre, outside the jurisdiction of ethics.

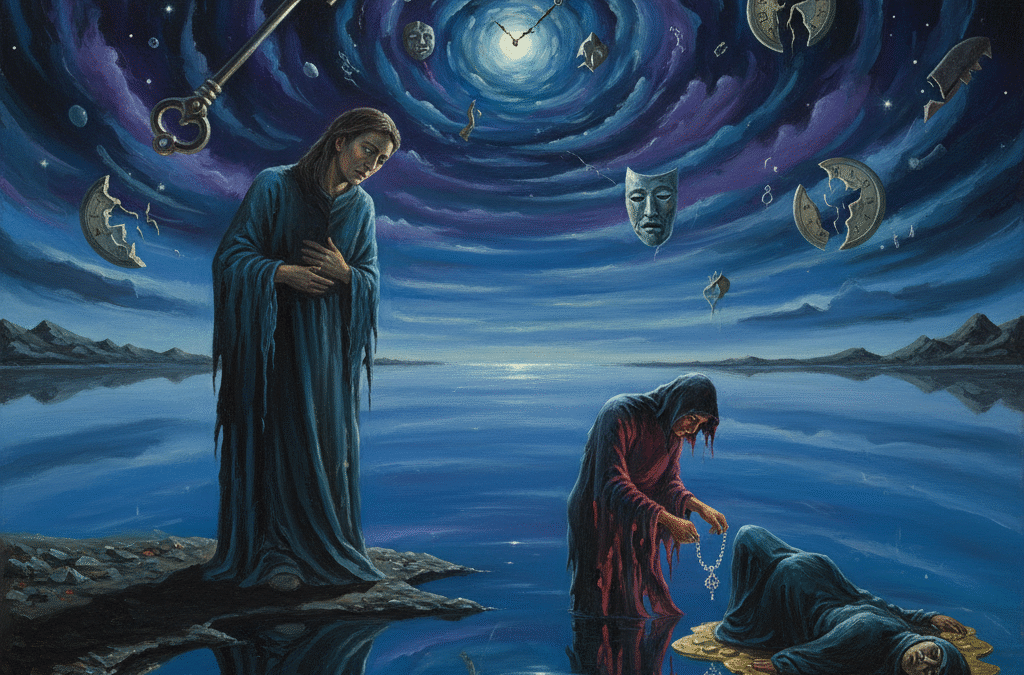

But there is a rebuttal that complicates this picture, dreams have a tendency to reveal what our conscious minds conceal. In dreaming, the logical censor evaporates, and desire, fear, and impulse rise to the surface. Freud famously held that dreams are “the royal road to the unconscious,” a gateway to the true self free of social pretense. If so, then what we do in dreams, even if not of our choosing, can still tell us something about our moral state within. A violent dream need not render us guilty of violence, but it can reveal underlying aggression. A dream of betrayal can warn of unseen temptation. Thus, dreams become moral introspection, challenging us to confront the parts of ourselves we deny.

But this interpretation is perilous if carried too far. Human beings cannot be defined by ephemeral images in the mind. Our selves are made up not simply by what we experience, but by how we behave on those feelings in everyday life. A taste for cruelty is not the same as cruelty; it is the restraint, the willingness to do something other than that which makes us ethical creatures. To confuse dream impulses with waking choices risks eliminating the distinction itself, and thus depriving morality of its purpose. If morality is a matter of blame and responsibility, then dreams, by withdraw us from actual agency, are beyond it.

Still, there are those who demand a middle ground. Perhaps, we are not morally at fault for what we do in dreams, but we are responsible to address how we interpret and integrate them subsequently. A betrayal dream may not damn us, but it will encourage us to question why this representation emerged. An aggressive dream can be warning us about anger hidden inside us. Here, dreams are ethically precious not as virtues or crimes in themselves, but as calls to higher self-knowledge. They are not moral successes or failures, but moral signs, messages of the unconscious that need to be noted upon awakening.

So are we to blame for dream deeds? Not in the same way we are guilty of our waking actions, but maybe the morality of dreams lies in how we greet them when sunlight returns. Do we reject them as meaningless shadows, or do we apply them in dealing with the deeper truths of ourselves? It is in that choice, the choice awake, not the choice dreamt, our duty begins.